The physical shape and structural arrangement of food portions influences how quickly they move through the digestive system. This article explores the mechanical factors that affect gastric processing and digestive timing.

Food Particle Size & Gastric Mixing

The stomach does not passively hold food; rather, it actively churns and mixes it with gastric secretions. This mechanical process breaks down food particles and aids chemical digestion. The size and shape of the original portion influences how effectively the stomach mixes and breaks down the food.

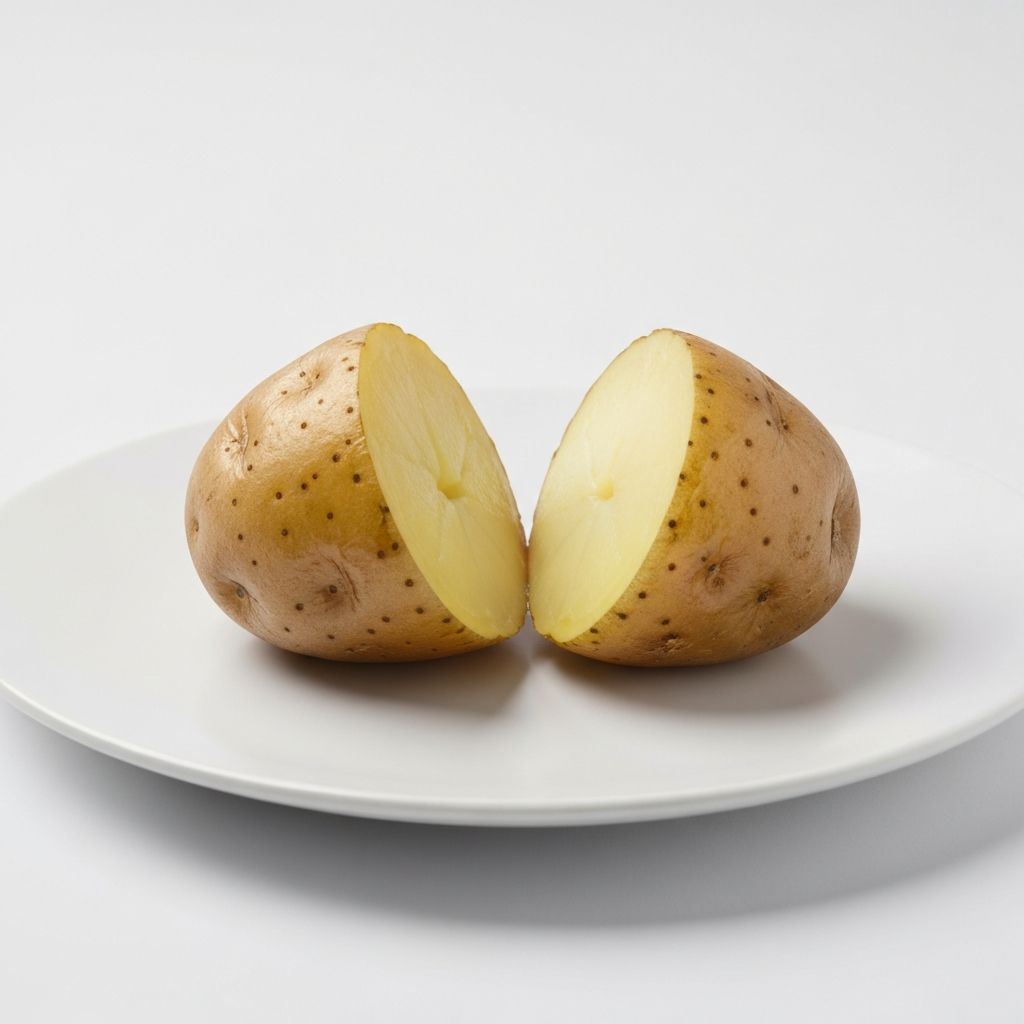

Larger, more cohesive portions create different compression patterns than fragmented, small portions. The stomach's muscular activity must work to break apart solid food structures, with different effort required for different portion geometries. A whole baked potato requires different gastric work than pre-diced potato pieces of equivalent weight.

Gastric Emptying Rates & Food Consistency

The rate at which the stomach propels food into the small intestine—called gastric emptying—depends partly on portion structure. The stomach controls emptying through the pyloric sphincter, a muscular valve that opens and closes to regulate flow. This valve's opening is influenced by the physical consistency of the stomach contents.

More liquid portions empty faster than solid portions of equivalent calories. A thick soup empties more slowly than water of identical volume. The stomach essentially meters out food particles in small units, and particle size affects how quickly this process occurs.

Surface Area & Chemical Breakdown

The surface area of food particles influences how quickly enzymes can access and break down nutrients. Portions that are already fragmented present more surface area for gastric enzymes to work on. Pre-cut vegetables have more surface area than whole vegetables of equivalent weight, influencing enzyme access and breakdown rate.

This is purely a mechanical property. More surface area allows faster enzyme action, which occurs independently of whether this is beneficial or detrimental from a physiological perspective.

Solid vs. Liquid Portions

Solid and liquid portions follow distinctly different pathways through the stomach. Pure liquids may bypass most of the stomach's mechanical processing and move quickly into the small intestine. Solid foods require significant mechanical breakdown before they can be emptied from the stomach.

This explains why liquid portions (soups, beverages, smoothies) result in faster nutrient absorption than solid portions of equivalent nutritional content. The mechanical requirements differ fundamentally based on portion physical state.

Macronutrient Effects on Emptying

In addition to physical shape, macronutrient composition powerfully influences gastric emptying. Fat-rich portions empty from the stomach slowly, with regulatory hormones (cholecystokinin) slowing gastric contractions. Protein portions empty at intermediate rates, while simple carbohydrate portions empty rapidly.

This means a high-fat solid portion empties slowly despite its structure, while a high-carbohydrate liquid portion empties very rapidly. The chemical composition modulates the mechanical emptying process significantly.

Fiber Content & Transit Time

Portions high in insoluble fiber (vegetables, whole grains) transit through the digestive system faster than portions low in fiber, all else equal. Fiber physically stimulates muscle contractions in the small intestine and colon, accelerating overall transit. Soluble fiber behaves differently, actually increasing viscosity and potentially slowing transit in some contexts.

Individual Variation in Digestion Timing

Significant individual variation exists in gastric emptying rates. Age, physical fitness, hormonal status, and certain medications influence how quickly portions move through the stomach. Older adults show slower gastric emptying on average, while individuals with diabetes may experience altered emptying rates.

Educational Context

This article describes factual observations about how portion geometry and composition influence digestive timing. These are purely descriptive mechanisms, not behavioral recommendations. Individual digestion varies significantly, and optimal portion structure depends on individual health status and goals.